The Legal Intelligencer

(by Lisa M. Bruderly)

On Dec. 11, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers (collectively, the agencies) released a long-awaited proposed rule that would redefine “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) under the Clean Water Act (CWA) and dramatically alter the federal government’s jurisdiction over surface water, including wetlands, throughout the United States. The Trump administration’s proposed rule is intended to replace the Obama administration’s 2015 rule defining WOTUS, known as the “Clean Water Rule” (CWR). The purpose of the 253-page proposed rule is to provide clarity, predictability and consistency in identifying federally regulated waters. The public comment period on the proposed rule will be open for 60 days after formal publication in the Federal Register.

Earlier WOTUS Actions by the Trump Administration

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has prioritized rolling back the CWR’s definition of WOTUS, which is widely regarded as expanding the scope of federal CWA jurisdiction. In February 2017, the president’s Executive Order 13778 directed the agencies to publish a proposed rule rescinding or revising the CWR and to consider defining WOTUS in a manner consistent with the narrower interpretation of WOTUS adopted in Justice Antonin Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715 (2006). Scalia’s opinion limits WOTUS to include only relatively permanent, standing or flowing bodies of water. In contrast, the CWR relied heavily on Justice Anthony Kennedy’s concurring opinion in Rapanos, which adopted a “significant nexus” test for CWA jurisdiction. These actions and others by the Trump administration and related judicial decisions have resulted in the current, unique and confusing situation in which the CWR is enjoined in 28 states but in effect in 22 others, including Pennsylvania.

Proposed WOTUS Rule

The agencies describe the proposed rule as “straightforward” and cost-effective, while still protective of navigable waters and consistent with statutory authority. However, the proposed WOTUS definition is considerably scaled back from the CWR definition and would mean less federally regulated waters.

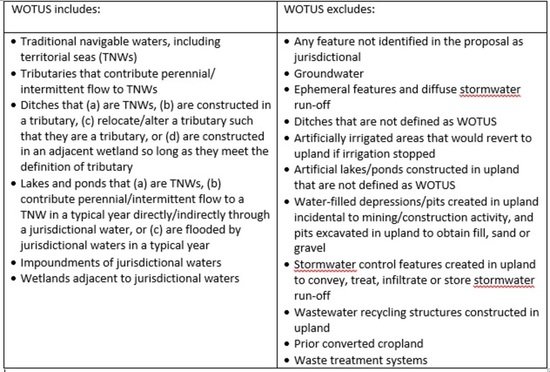

The proposal focuses on waters that are “physically and meaningfully connected to traditional navigable waters.” Unlike the CWR, which separates waters into those that are jurisdictional either by rule or on a case-by-case basis (i.e., by significant nexus), the proposed rule identifies six categories of waters that are WOTUS and 11 categories of waters/features that are not WOTUS, as summarized below:

The proposed rule materially changes the CWR definition of WOTUS in several ways, including the following

- “Significant nexus” is absent—The proposed rule does not reference waters with a “significant nexus” to TNWs, a hallmark of the CWR. Instead, the proposed WOTUS definition would focus largely on whether the water has a “surface connection” or contributes perennial/intermittent flow to a TNW.

- “Tributary” is narrowed—The proposed definition of a “tributary” is limited to naturally occurring surface water channels with perennial/intermittent flow to a WOTUS in a typical year either directly or indirectly through another WOTUS. Ephemeral streams and references to defined beds/banks are absent from the proposed definition.

- “Adjacent Wetland” is narrowed—“Adjacent wetlands” (as defined in the Proposed Rule) would only be jurisdictional if they either physically abut a WOTUS or have a direct hydrologic surface connection to another WOTUS other than a wetland. In contrast, under the CWR, jurisdiction extended to wetlands that are physically separated from a WOTUS but within a certain distance from an ordinary high water mark or within the 100-year floodplain of a WOTUS.

- “Typical year” defined—Under the Proposed Rule, federal jurisdiction over tributaries, lakes, and adjacent wetlands and the proposed definitions of perennial/intermittent streams would be determined based on the conditions during a “typical year.” “Typical year” is defined as the “normal range of precipitation over a rolling 30-year period for a particular geographic area.”

- New definitions for “waste treatment systems” and “prior converted cropland”—The Proposed Rule includes a new definition of “waste treatment systems” that would exclude from federal jurisdiction all components of such lawfully constructed systems designed to actively or passively treat wastewater. The Proposed Rule also clarifies when “prior converted cropland” would be abandoned and, therefore, no longer subject to the existing CWA exclusion.

Opportunities for Comment

If adopted as proposed, the proposed definition of WOTUS would fundamentally alter, and substantially narrow, the scope of the federal government’s authority under the CWA. Interested parties are encouraged to provide comments to the Agencies during the upcoming 60-day comment period. In addition, the agencies have scheduled a public webcast on Jan. 10, and a public listening session in Kansas City, Kansas on Jan. 23.

The agencies are specifically soliciting comments on several key aspects of their proposal, including whether:

- The significant nexus test must be a component of the proposed new definition of WOTUS.

- The definition of “tributary” should be limited to perennial waters and not those with intermittent flows.

- “Effluent-dependent streams” should be included in the definition of tributary.

- The jurisdictional cut-off for “adjacent wetlands” should be within the wetland or at the wetland’s outer limits.

- A ditch can be both a “point source” and a WOTUS.

- The agencies should work with states to develop, and make publicly available, state-of-the-art geospatial data tools to identify the locations of WOTUS.

Continuing Uncertainty

It is important to highlight that the proposed rule, while significant, is far from a final step in what undoubtedly will be a lengthy process to redefine WOTUS. As with the CWR, litigation challenging any final rule adopting all or part of the proposal is certain. For example, litigation regarding the CWR began almost immediately upon finalization of the CWR in 2015 and continues today. Until this proposal works its way through the rulemaking process and the CWR challenges work their way through the courts, regulated parties must contend with state-dependent differences in the scope of federal authority under the CWA. These nuances can have significant permitting, compliance, and enforcement implications.

Babst Calland is actively monitoring this rulemaking and is analyzing how it could affect industrial, commercial and municipal clients across the country.

For the full article, click here.