Environmental Alert

(by Lisa Bruderly and Gary Steinbauer)

On April 23, 2019, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published a Federal Register notice of availability of an Interpretive Statement[1] concluding that it considers releases of pollutants to groundwater to be categorically excluded from the Clean Water Act’s permitting requirements. The notice opens a 45-day public comment period, ending on June 7, 2019. EPA is requesting comments on the analysis and rationale included in the Interpretive Statement and is soliciting input on additional actions that may be needed to provide further clarity and regulatory certainty on whether the NPDES permit program regulates releases of pollutants to groundwater. The publication of the Interpretive Statement has reinjected EPA into the ongoing debate, federal circuit court split, and pending U.S. Supreme Court case over whether the CWA’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit program regulates point source discharges that travel through groundwater before reaching a jurisdictional surface water.

Content and Reasoning Behind the Interpretive Statement

EPA describes the Interpretive Statement as the Agency’s “most comprehensive analysis” of the CWA’s text, structure, and legislative history as they relate to whether the NPDES permit program governs point source releases to groundwater. The bulk of the 63-page Interpretive Statement includes EPA’s legal analysis of the statutory provisions implementing and enforcing the NPDES permit program, the forward-looking, information-gathering statutory provisions that explicitly reference groundwater, and legislative history. Based on its analysis of this information, EPA concludes that Congress deliberately chose to exclude discharges of pollutants to groundwater from the NPDES permit program, even when those pollutants are conveyed to a jurisdictional surface water via groundwater.

While EPA’s conclusion is based primarily on its legal interpretation of the CWA, the major policy-based rationale supporting its conclusion is that groundwater is extensively regulated under other federal and state statutory regimes. With respect to state laws and regulations that limit discharges to groundwater, EPA notes that several states have laws in place that protect groundwater. On the federal side, EPA notes that the Safe Drinking Water Act, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act all regulate groundwater quality to some extent. According to EPA, these federal and state laws and regulations are sufficient to protect groundwater.

Conflict with the Existing Circuit Court Opinions and Pending Supreme Court Appeal

EPA describes its position in the Interpretive Statement as differing from the two legal theories that emerged from the numerous 2018 federal appellate court decisions addressing whether the CWA regulates point source discharges that travel through groundwater before reaching a jurisdictional surface water. Unlike the decisions of the Fourth and Ninth Circuits and EPA’s prior statements that have been construed as advocating a different interpretation, EPA now unequivocally believes that any release of a pollutant to groundwater does not fall within the ambit of the CWA. Thus, EPA has rejected the “direct hydrological connection” legal test established by the Fourth Circuit in Upstate Forever v. Kinder Morgan[2] and the “fairly traceable” legal test established by the Ninth Circuit in Hawai’i Wildlife Fund v. County of Maui[3] and will apply the Interpretive Statement in all jurisdictions, other than those 14 states (including West Virginia, Virginia and Maryland) and other territories within the Fourth and Ninth Circuits.[4] The decisions of the Fourth and Ninth Circuits will stand until further clarification by the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed to hear the County of Maui appeal approximately two months ago.

In the Ninth Circuit’s County of Maui v. Hawai’i Wildlife Fund decision, the Court affirmed the district court’s decision finding the County liable under the CWA for injecting treated sanitary wastewater into separately permitted underground wells after the plaintiffs demonstrated that the discharge ultimately reached the Pacific Ocean. On appeal, the Supreme Court will be deciding “whether the CWA requires a permit when pollutants originate from a point source but are conveyed to navigable waters by a nonpoint source, such as groundwater.” The Court granted the County’s petition for review after the United States filed an amicus brief, in which it noted that EPA would soon be publishing what we now know is the Interpretive Statement.

It is unclear what role, if any, EPA’s Interpretive Statement will play in the County of Maui matter. The County’s merits brief currently is due before the close of the public comment period on the Interpretive Statement. It is also unclear whether EPA will finalize any rulemaking or take any other more formal administrative action before the Supreme Court renders its decision, likely in 2020 after oral arguments are heard this fall.[5] Furthermore, the level of deference, if any, the Supreme Court will give EPA on its position in the Interpretive Statement is unclear, particularly because the position articulated in the Interpretive Statement is inconsistent with the position that the United States, on behalf of EPA, took in an amicus brief filed when the County of Maui case was previously heard by the Ninth Circuit.

In the meantime, regulated parties outside the Fourth and Ninth Circuits now have additional support to defend against lawsuits alleging that the CWA regulates point sources discharges that travel through groundwater before reaching a jurisdictional surface water.

Babst Calland is actively monitoring this Interpretive Statement and evaluating its potential effect across sectors and industries. If you have questions about the Interpretive Statement or comment procedures, please contact Lisa M. Bruderly at (412) 394-6495 or lbruderly@babstcalland.com or Gary E. Steinbauer at (412) 394-6590 or gsteinbauer@babstcalland.com.

Firm Alert

(by Jean Mosites and Kevin Garber)

On April 16, 2019, the Pennsylvania Environmental Quality Board, in a vote of 14-5, directed the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection to develop a report and recommendation on a petition for a cap and trade regulation. The Clean Air Council, Widener Commonwealth Law School Environmental Law and Sustainability Center, and others submitted the Petition on February 28, 2019 asking EQB to promulgate a regulation that would create a multi-sector cap and trade system to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to achieve carbon neutrality in Pennsylvania by 2052.

The Petition

The Petition includes a fully drafted regulation that establishes a cap on covered GHG emissions, based on a 2016 base year, and reduces GHG emissions to carbon neutrality by 2052. The regulation borrows heavily from the California cap and trade regulation, which is a multi-sector program that includes Ontario and Quebec. The California regulation, however, does not require a reduction of all GHG emissions to net zero.

Citing a goal set by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement, the regulation proposes a cap on Pennsylvania GHG emissions to begin at 91 percent of 2016 emissions and thereafter decline by three percent each year until reaching net zero emissions by 2052. Covered entities would be required to obtain allowances, by auction or allocation, for each metric ton of reportable GHG emissions per year attributable to their operations in Pennsylvania. Allowances would cost a minimum of $10 each in 2020, with the price increasing by 10 percent plus the rate of inflation each year. Any person may buy from the available allowances regardless of whether that person must surrender allowances for GHG emissions or not.

The petitioners cite the Pennsylvania Air Pollution Control Act and the Environmental Rights Amendment, Article I, Section 27 of the Pennsylvania Constitution, as legal authority for their Petition. The only express Pennsylvania legislation related to climate change and greenhouse gases is the Pennsylvania Climate Change Act, Act 70 of 2008, which simply provides for a report on potential climate change impacts, the duties of DEP, establishment of a Climate Change Advisory Committee, and a voluntary registry of GHG emissions. Neither the Air Pollution Control Act nor the Climate Change Act provides express authority to regulate GHG emissions or establish a cap and trade system. The Petition bypasses legislative consideration of this issue by asking EQB as an administrative body to promulgate a climate change regulation.

Next Steps

DEP will prepare a report and recommendation within 60 days (or longer if the report cannot be completed within 60 days) on whether EQB should promulgate a cap and trade regulation. The report should comprehensively evaluate the social, environmental and economic impacts of the proposed regulation, a task that will require significant inquiry as well as sweeping speculation. EQB members asked for updates and status reports from DEP if the report is not completed by its next meeting in June. If EQB decides to promulgate a GHG regulation, EQB policy directs DEP to prepare a proposed rulemaking for EQB’s consideration within six months after mailing the report to the petitioners.

This Petition and its proposed regulation present a dramatic departure from any current regulation in Pennsylvania and are intended to affect every aspect of the economy of this Commonwealth. Whether or not such a program in Pennsylvania would have any effect on the global climate is a question that no one can answer. Babst Calland will continue to track and report on this and related issues as they develop in the coming months.

If you have questions about the petition for cap and trade regulation, please contact Jean M. Mosites at (412) 394-6468 or jmosites@babstcalland.com or Kevin J. Garber at (412) 394-5404 or kgarber@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

Environmental Alert

(by Donald Bluedorn and Gary Steinbauer)

On April 12, 2019, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a decision in Southwestern Electric Power Company, et al. v. EPA, addressing pending claims in consolidated petitions challenging the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s revised effluent limitations guidelines for the Steam Electric Power Generating Point Source Category (ELGs). The Opinion vacated the “legacy” wastewater and “combustion residual leachate” best available technology economically achievable (BAT) standards promulgated by EPA in 2015. A copy of the Opinion is available here: http://www.ca5.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/15/15-60821-CV0.pdf.

Under the Clean Water Act (CWA), EPA is responsible for establishing nationwide technology-based standards to govern discharges of pollutants by specific industrial categories. See 33 U.S.C. § 1314(b). In November 2015, EPA promulgated revisions to the ELGs after a multi-year study of wastewater management and treatment technologies used by steam-electric power plants since the ELGs were last revised in 1982. EPA revised the ELGs to regulate six separate wastewater streams: (1) flue gas desulfurization (FGD) wastewater; (2) fly ash transport wastewater; (3) bottom ash transport wastewater (BATW); (4) flue gas mercury control wastewater; (5) combustion residual leachate (leachate); and (6) gasification wastewater. In addition, the ELGs regulate “legacy” wastewater, which consists of one or more of the above-referenced wastewater streams (commingled or separate) if they are generated before the date determined by the state permitting authority. For leachate and “legacy” wastewaters, EPA selected impoundments as BAT-level controls. By contrast, EPA affirmatively rejected surface impoundments as BAT for the other five wastewater streams and imposed limits based on other forms of wastewater treatment or management.

In granting the environmental groups’ challenge to the BAT “legacy” wastewater limits in the ELGs, the Court repeatedly emphasized what it felt was a false distinction that EPA created between “legacy” wastewater and the other wastewater streams regulated under the ELGs. As noted, “legacy” wastewaters are defined solely by when the wastewater was generated. Relying primarily on EPA’s inconsistent determinations that impoundments constitute BAT for “legacy” wastewaters yet are considered ineffective and outdated (i.e., not BAT) for the same subsets of wastewaters, the Court held that EPA’s BAT determination for “legacy” wastewaters was arbitrary and capricious.

The Court also rejected EPA’s argument that it lacked data to justify adopting a more advanced treatment technology as BAT for “legacy” wastewaters. In the rulemaking record for the ELGs, EPA acknowledged that multiple power plants have been using chemical precipitation to treat “legacy” wastewaters. The Court also cited numerous instances within the rulemaking where EPA concluded that impoundments are ineffective at removing toxic pollutants. Notwithstanding the typical deference EPA receives in setting BAT limitations, the Court held that EPA’s undisputed statements and scientific conclusions from its own rulemaking record were enough to conclude that using surface impoundments as BAT for “legacy” wastewaters was unlawful under the CWA.

The Court essentially came to the same conclusion when it vacated EPA’s BAT limitations for leachate. For leachate, EPA adopted impoundments as the technology for BAT-level control in its 2015 revisions; the same technology EPA adopted as the BPT-level of control for leachate when it revised the ELGs in 1982. The CWA provides that BPT is to be the “average of the best performance levels of existing plants,” whereas BAT is to represent the performance of the “single best-performing plant in an industrial sector.” According to the Court, EPA unlawfully conflated the more stringent BAT limits with the less stringent BPT when it adopted the 1982 BPT limits at BAT for leachate in 2015. The Court also rejected EPA’s attempt to justify the leachate BAT determination based on the relatively small amount of pollutants discharged in leachate and the stricter BAT requirements for the other, more voluminous waste streams. Consequently, even if the CWA allowed EPA to establish BAT for leachate as the previously establish BPT for the same wastewater stream, the Agency’s reasons for doing so were consisted arbitrary and capricious.

The Court’s decision in Southwestern Electric is another significant blow to an EPA rulemaking for the electric power industry. As reported in our past Alert, the D.C. Circuit recently vacated and remanded significant portions of EPA’s 2015 Coal Combustion Residuals (CCR) Rule, which regulates, among other things, surface impoundments holding CCR generated by power plants. In addition, the Southwestern Electric decision was issued in the midst of EPA’s efforts to revise the ELGs’ BAT requirements for FGD wastewater and BATW. The Agency previously indicated that it intends to propose revised requirements for the FGD wastewater and BATW BAT requirements in 2019. EPA could seek reconsideration or ask the Supreme Court to review the Southwestern Electric Opinion, which could take several months. In short, time will tell whether the Fifth Circuit’s vacatur and remand of the BAT limits for “legacy” wastewater and leachate will impact EPA’s projected timeline for reconsideration of the BAT requirements for FGD wastewater and BATW.

If you have any questions about the Fifth Circuit’s April 12, 2019 Opinion, please contact Donald C. Bluedorn II at (412) 394-5450 or dbluedorn@babstcalland.com or Gary E. Steinbauer at (412) 394-6590 or gsteinbauer@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

Pipeline Safety Alert

(by James Curry, Keith Coyle and Brianne Kurdock)

On April 10, 2019, President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order on Promoting Energy Infrastructure and Economic Growth (Executive Order). In addition to outlining U.S. policy toward private investment in energy infrastructure and directing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to take certain actions to improve the permitting process under the Clean Water Act, the Executive Order instructs the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) to update the federal safety standards for liquefied natural gas (LNG) facilities. The Executive Order notes that DOT originally issued those safety standards nearly four decades ago and states that the current regulations are not appropriate for “modern, large-scale liquefaction facilities[.]” Accordingly, the Executive Order directs DOT to finalize new LNG regulations within 13 months, or by no later than May 2020, an ambitious deadline given the complex issues involved and typical timeframe for completing the federal rulemaking process.

What is LNG?

LNG is natural gas that is cooled through a liquefaction process to minus 260 degrees Fahrenheit. Natural gas converts to a liquid state at that temperature and occupies a volume that is 600 times smaller than its gaseous counterpart. The reduced volume and high energy density of LNG makes long-distance transportation commercially viable, particularly to markets that lack access to local supplies of natural gas. LNG facilities create three primary risks from a safety perspective. As a cryogenic liquid, LNG can cause frostbite or severe burns upon contact with skin. LNG also vaporizes when released into the environment and can ignite in certain air-gas mixtures. High concentrations of LNG vapors may displace oxygen, creating the risk of asphyxiation in confined spaces.

Why Does DOT Regulate LNG Safety?

The LNG industry has a long history in the United States. The first LNG plant went into service in West Virginia in the World War I era, and a commercial liquefaction plant in Cleveland, Ohio went into operation in the 1940s. In 1944, the Cleveland plant experienced an LNG tank failure that led to a fatal explosion and fire and resulted in extensive property damage. The first commercial shipment of LNG by vessel occurred 15 years later, in 1959, when the Methane Pioneer sailed from Louisiana to the United Kingdom. Several large-scale LNG terminals were constructed during the late 1960s and 1970s in places like Alaska, Louisiana, Georgia, Maryland, and Massachusetts, a period that coincided with DOT’s initial efforts to establish federal safety standards for LNG facilities.

In the Natural Gas Pipeline Safety Act of 1968 (1968 Act), the U.S. Congress authorized DOT to prescribe and enforce minimum federal safety standards for gas pipeline facilities and persons engaged in the transportation of gas. Acting pursuant to the authority provided in the 1968 Act, DOT promulgated interim federal safety regulations for LNG facilities in the early 1970s. The interim regulations required operators to comply with the 1972 edition of the National Fire Protection Association Standard 59A (NFPA 59A), a consensus industry standard for the production, handling and storage of LNG, as well as DOT’s new federal safety standards for gas pipeline facilities.

After issuing the interim regulations, DOT initiated a new rulemaking proceeding to establish permanent federal safety standards for LNG facilities. DOT relied on NFPA 59A in developing those standards, including the concept of requiring an operator or governmental authority to exercise control over the activities that occur within a specified distance of an LNG facility. These distances, known as “exclusion zones,” were designed to protect the public from unsafe levels of thermal radiation and vapor gas dispersion in the event of an LNG incident. DOT proposed to require that operators calculate the dimensions of an exclusion zone using certain mathematical models and other parameters.

While DOT’s LNG rulemaking proceeding was still underway, Congress passed the Pipeline Safety Act of 1979 (1979 Act). In addition to expanding DOT’s authority to regulate hazardous liquid pipeline facilities, the 1979 Act included a rulemaking mandate directing DOT to finalize the new regulations for LNG facilities. DOT satisfied that mandate in August 1980 by issuing the original version of federal safety standards for LNG facilities. The regulations, codified at 49 C.F.R. Part 193, incorporated the 1979 edition of NFPA 59A by reference and included siting requirements for LNG facilities based on the exclusion-zone approach. Other provisions addressed design, construction, operation, maintenance, security, and fire protection.

DOT left the original Part 193 regulations in place for the next two decades as unfavorable market conditions significantly reduced domestic interest in LNG development, particularly for large-scale terminals. In 2000, DOT responded to a rulemaking petition from NPFA by repealing many of its substantive regulations and deferring to the comparable provisions in the 1996 edition of NFPA 59A. In subsequent industry standards updates, DOT incorporated the 2001 edition and 2006 editions of NFPA 59A into Part 193. No other significant changes to the LNG regulations have occurred since DOT issued the original federal safety standards in 1980.

Why is President Trump Focusing on DOT’s LNG Regulations?

DOT’s LNG-related activities have increased significantly in recent years, primarily in response to the rapid growth of U.S. natural gas resources and renewed interest in domestic LNG projects. In the Obama administration, DOT issued several significant letters of interpretation dealing with the Part 193 siting requirements and approved the use of two alternative vapor gas dispersion models for calculating exclusion zone distances. DOT also issued a series of Frequently Asked Questions providing operators with guidance on LNG issues and created a process for reviewing design spill determinations for proposed LNG projects. In August 2018, DOT and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the federal agency that exercises economic regulatory and limited safety jurisdiction over LNG terminals and facilities under the Natural Gas Act of 1938, executed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to improve interagency coordination. Under the MOU, DOT is responsible for issuing a letter of determination on whether a proposed FERC-jurisdictional LNG project complies with the Part 193 regulations.

The Executive Order seeks to build on these recent efforts by directing DOT to update the Part 193 regulations by no later than May 2020. DOT will need to consider several important issues during the rulemaking process, such as whether to incorporate more recent additions of NFPA 59A into Part 193 by reference, whether changes should be made to the exclusion zone approach in the siting regulations, and whether to address a new rulemaking mandate for small-scale LNG facilities that Congress included in the 2016 reauthorization of the Pipeline Safety Act. Finishing the rulemaking process by the deadline provided in the Executive Order will be extremely difficult. DOT has not yet issued a notice of proposed rulemaking, and the proceeding is likely to generate significant public interest. Industry has made tremendous technological advances in the four decades since DOT’s last comprehensive review of its LNG regulations, and public interest and other advocacy groups have also become very active in recent proceedings related to new LNG projects. These factors, when combined with the ordinary time horizon for completing DOT rulemaking proceedings and upcoming presidential election, suggest that extraordinary efforts will be needed to issue a final rule in the next 13 months.

Click here for PDF.

Employment Alert

(by John McCreary and Stephen Antonelli)

|

| Under the current law, for an employee to be exempt from the FLSA’s overtime provisions, he or she must earn at least $23,660 per year ($455 per week) on a “salary basis” and perform the job duties described in the executive, administrative, professional and other exemption categories recognized by DOL. If enacted, that salary threshold would rise to $35,308 ($679 per week) under the new rule, which could become effective in January 2020.

The job duties tests will not change. This salary increase would mark the first increase in the salary threshold since 2004. The new rule would enable approximately one million more employees to earn overtime pay. A more drastic increase to the threshold was approved by the Obama administration and blocked by a federal judge in Texas shortly before it was to become effective. That increase would have doubled the salary threshold and enabled over four million additional employees to be eligible to earn overtime.

In addition to increasing the overtime salary threshold, the final rule would also:

- increase the total annual compensation requirement for highly compensated employees (HCE) from $100,000 to $147,414;

- maintain overtime protections for police officers, fire fighters, paramedics, nurses, and laborers including, non-management production-line employees and non-management employees in maintenance, construction and similar occupations such as carpenters, electricians, mechanics, plumbers, iron workers, craftsmen, operating engineers, longshoremen, and construction workers; and

- make a commitment to periodically review the salary threshold, although any update would not be automatic and would continue to require notice-and-comment rulemaking.

More information about the proposed rule is available at www.dol.gov/whd/overtime2019. Babst Calland’s Employment and Labor Group will continue to keep employers apprised of further developments related to this and other employment and labor topics. If you have any questions or need assistance in addressing the above-mentioned area of concern, please contact John A. McCreary, Jr. at (412) 394-6695 or jmccreary@babstcalland.com, or Stephen A. Antonelli (412) 394-5668 or santonelli@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF. |

Environmental Alert

(by Lindsay P. Howard, Alana E. Fortna and Matthew C. Wood)

On February 14, 2019, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its Action Plan for regulating and addressing risks concerning per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), comprising a group of synthetic chemicals with widespread consumer, commercial, and industrial applications. PFAS refers to a large collection of man-made chemicals that includes PFOA and PFOS (both specifically targeted in the Action Plan), as well as PFBS, perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), and others referred to as GenX chemicals, and thousands of other compounds. Although there have been only limited widespread studies, evidence suggests that exposure to some PFAS chemicals can lead to adverse health effects. PFAS have been widely-used since as early as the 1940s, but public and governmental interest has grown, especially in the last decade, as concerns regarding the potential effects of exposure to PFAS have increased.

Although the Action Plan generally tends to focus on drinking water, EPA notes that exposure may occur through, among other things, consumption of plants and meat in which PFAS have bioaccumulated, consumption of food exposed to PFAS, exposure to commercial and consumer products such as non-stick cookware, stain-resistant carpet and clothing, and pizza boxes. According to EPA, the ubiquitous nature of PFAS means that most people have been exposed to PFAS chemicals. In the environment, PFAS have been found in dozens of states, as well as on military bases and tribal land.

EPA developed the Action Plan in response to more than 120,000 comments in the public docket and feedback from federal, state, and local stakeholders who attended the Agency’s two-day National Leadership Summit on PFAS in Washington, D.C. EPA also gathered input by visiting and engaging with members of PFAS-affected communities in several states. In a press conference to announce the Action Plan, EPA Acting Administrator Andrew Wheeler said, “The PFAS Action Plan is the most comprehensive cross-agency plan to address an emerging chemical of concern ever undertaken by EPA.” With that said, several states and other stakeholders believe that EPA’s efforts are too slow and are therefore moving ahead with their own regulatory and other responses to PFAS.

Painted in broad strokes, the Action Plan focuses on: (1) developing a better understanding of PFAS; (2) addressing current PFAS contamination; (3) preventing future PFAS contamination; (4) and keeping the public informed about PFAS. To accomplish these objectives, the Agency has set priority goals, short-term goals (those that can be accomplished in less than two years), and long-term goals (those that will take longer than two years to accomplish).

One of EPA’s immediate priorities is to evaluate whether maximum contaminant levels (MCLs) for two of the more common PFAS – PFOA and PFOS – should be established under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA). While acknowledging that the regulatory process for establishing MCLs can be lengthy and uncertain, Administrator Wheeler anticipated that the first step in the process could be completed by the end of 2019. It should be noted that this first step is only a threshold determination under the SDWA and will not necessarily result in the establishment of enforceable MCLs in the future.

The Agency is also evaluating methods for classifying PFAS as “hazardous substances” under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as Superfund. Doing so would allow EPA and other federal agencies to hold responsible parties accountable and more fully utilize cleanup and cost recovery authority under CERCLA. With that said, EPA is already using available enforcement tools to address PFAS as circumstances dictate.

Another EPA goal is to develop interim cleanup recommendations for groundwater contaminated with PFOA and PFOS that will provide guidance at sites being investigated and/or cleaned up under CERCLA or the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, while also serving as helpful guidance for other agencies, states, tribes, and other entities. At this time, EPA routinely uses a Health Advisory Level (HAL) of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) as a target cleanup level for PFAS.

Longer term, EPA plans on gathering and/or relying on data and information to determine whether regulation of PFAS is appropriate under various other regulatory schemes, including listing PFAS to the Toxics Release Inventory or developing ambient water quality criteria for human health under Clean Water Act Section 304(a). For curating and sharing data, EPA proposes creating data standards best practices for PFAS monitoring data and researching, identifying, and understanding other ecological impacts of PFAS in the environment.

As noted above, in the wake of perceived inaction by EPA, several states have pushed forward with their own response to PFAS compounds. For example, New Jersey is currently developing the nation’s first MCLs and groundwater quality standards for PFOA and PFOS, at proposed levels that are far more stringent than EPA’s current HAL of 70 ppt (proposed at 14 ppt and 13 ppt, respectively). Similarly, Pennsylvania recently established its PFAS Action Team, a multidisciplinary group that is charged with comprehensively evaluating and addressing the perceived risks presented by PFAS compounds. Several Pennsylvania sites have already been targeted by the Team for additional investigation and potential response. Many other states are initiating their own studies and regulatory response to this growing problem as well. As a result, it is likely that the regulatory community will be facing inconsistent approaches to PFAS across the country even as EPA initiates its Action Plan.

These recent regulatory developments with respect to PFAS and other emerging contaminants (e.g., 1,4 dioxane) are having profound impacts on a number of fronts. For example, many sites that may have already been fully investigated and/or remediated may be subject to new requirements, including further evaluation/characterization of PFAS compounds. At most of these sites, PFAS were not even considered when prior work scopes or remedial alternatives were initially established. As a result, many of our clients have found that some evaluation of PFAS will be required before final regulatory closure is permitted. Routine environmental due diligence in commercial transactions (i.e., ASTM Phase 1 studies) will similarly be complicated by these newly identified compounds and the relative lack of information relating to them.

Despite the bold pronouncements in EPA’s Action Plan, the steps EPA identifies are merely the first of many that will be required to address PFAS across the country. Nonetheless, by the end of 2019, stakeholders should have at least some idea as to the progress EPA is making in implementing its Plan. What is clear, however, is that the states will not be waiting around to see if EPA actually takes the steps it has identified in its Action Plan.

Babst Calland will continue to track EPA’s and the states’ dynamic plans to identify, regulate and respond to PFAS in our communities. If you have any questions regarding the EPA’s Action Plan, specific state responses, or other environmental laws pertaining to PFAS, please contact Lindsay P. Howard at (412) 394-5444 or lhoward@babstcalland.com, Alana E. Fortna at (412) 773-8702 or afortna@babstcalland.com, or Matthew C. Wood at (412) 394-6589 or mwood@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

Environmental Alert

(by Lisa M. Bruderly and Gary E. Steinbauer)

On February 14, 2019, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers’ proposed rule to revise the definition of “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) under the Clean Water Act (CWA) was published in the Federal Register. The publication begins a 60-day public comment period, which ends on April 15, 2019, and comes more than two months after the Agencies released the proposed revised definition of WOTUS to the public on December 11, 2018. A detailed description of the proposed revised definition of WOTUS was covered in our previous Environmental Alert.

The Agencies are seeking comments on all aspects of their proposal, including the six categories of waters that would categorically be considered to be WOTUS, the 11 categories of waters or features that would not be considered to be WOTUS, and the newly proposed definitions of the terminology referenced in the proposal, such as “tributary” and “adjacent wetland.” In addition, the Agencies have specifically requested comments on the following issues:

- Whether the “significant nexus” test must be a component of the proposed new definition of WOTUS.

- Whether the definition of “tributary” should be limited to perennial waters only and not those with intermittent flows.

- Whether “effluent-dependent streams” should be included in the definition of “tributary.”

- Whether the jurisdictional cut-off for “adjacent wetlands” should be within the wetland or at the wetland’s outer limits.

- Whether a ditch can be both a “point source” and a WOTUS under the CWA.

- Whether the Agencies should work with states to develop, and make publicly available, state-of-the-art geospatial data tools that could be used to identify the locations of WOTUS.

- The appropriate field methodologies for identifying perennial or intermittent flow and navigability.

The proposed new definition of WOTUS would replace the 2015 Clean Water Rule (CWR) definition. As compared with the CWR, the proposed new definition of WOTUS would substantially narrow the scope of the federal government’s jurisdiction under the CWA. The proposed new definition of WOTUS is of particular importance to affected industries and municipalities in Pennsylvania and Ohio and the other 20 states where the CWR’s more expansive definition of WOTUS currently is in effect.

Babst Calland is actively monitoring this rulemaking and evaluating its potential effect across sectors and industries. If you have questions about the proposed rule or comment procedures, please contact Lisa M. Bruderly at (412) 394-6495 or lbruderly@babstcalland.com or Gary E. Steinbauer at (412) 394-6590 or gsteinbauer@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

The Legal Intelligencer

(by Lisa M. Bruderly)

On Dec. 11, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Army Corps of Engineers (collectively, the agencies) released a long-awaited proposed rule that would redefine “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) under the Clean Water Act (CWA) and dramatically alter the federal government’s jurisdiction over surface water, including wetlands, throughout the United States. The Trump administration’s proposed rule is intended to replace the Obama administration’s 2015 rule defining WOTUS, known as the “Clean Water Rule” (CWR). The purpose of the 253-page proposed rule is to provide clarity, predictability and consistency in identifying federally regulated waters. The public comment period on the proposed rule will be open for 60 days after formal publication in the Federal Register.

Earlier WOTUS Actions by the Trump Administration

Since taking office, President Donald Trump has prioritized rolling back the CWR’s definition of WOTUS, which is widely regarded as expanding the scope of federal CWA jurisdiction. In February 2017, the president’s Executive Order 13778 directed the agencies to publish a proposed rule rescinding or revising the CWR and to consider defining WOTUS in a manner consistent with the narrower interpretation of WOTUS adopted in Justice Antonin Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715 (2006). Scalia’s opinion limits WOTUS to include only relatively permanent, standing or flowing bodies of water. In contrast, the CWR relied heavily on Justice Anthony Kennedy’s concurring opinion in Rapanos, which adopted a “significant nexus” test for CWA jurisdiction. These actions and others by the Trump administration and related judicial decisions have resulted in the current, unique and confusing situation in which the CWR is enjoined in 28 states but in effect in 22 others, including Pennsylvania.

Proposed WOTUS Rule

The agencies describe the proposed rule as “straightforward” and cost-effective, while still protective of navigable waters and consistent with statutory authority. However, the proposed WOTUS definition is considerably scaled back from the CWR definition and would mean less federally regulated waters.

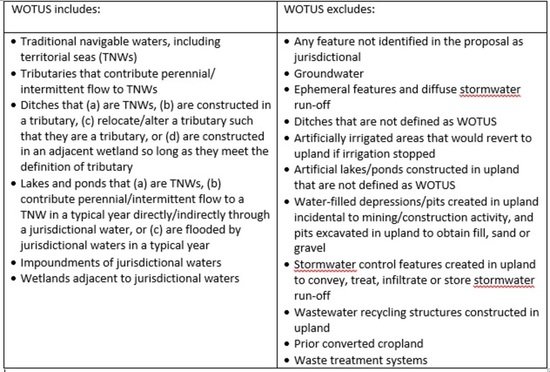

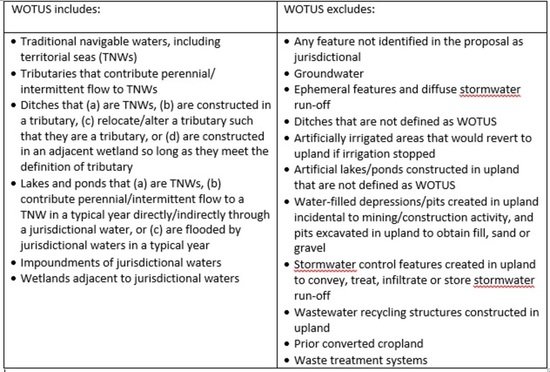

The proposal focuses on waters that are “physically and meaningfully connected to traditional navigable waters.” Unlike the CWR, which separates waters into those that are jurisdictional either by rule or on a case-by-case basis (i.e., by significant nexus), the proposed rule identifies six categories of waters that are WOTUS and 11 categories of waters/features that are not WOTUS, as summarized below:

The proposed rule materially changes the CWR definition of WOTUS in several ways, including the following

- “Significant nexus” is absent—The proposed rule does not reference waters with a “significant nexus” to TNWs, a hallmark of the CWR. Instead, the proposed WOTUS definition would focus largely on whether the water has a “surface connection” or contributes perennial/intermittent flow to a TNW.

- “Tributary” is narrowed—The proposed definition of a “tributary” is limited to naturally occurring surface water channels with perennial/intermittent flow to a WOTUS in a typical year either directly or indirectly through another WOTUS. Ephemeral streams and references to defined beds/banks are absent from the proposed definition.

- “Adjacent Wetland” is narrowed—“Adjacent wetlands” (as defined in the Proposed Rule) would only be jurisdictional if they either physically abut a WOTUS or have a direct hydrologic surface connection to another WOTUS other than a wetland. In contrast, under the CWR, jurisdiction extended to wetlands that are physically separated from a WOTUS but within a certain distance from an ordinary high water mark or within the 100-year floodplain of a WOTUS.

- “Typical year” defined—Under the Proposed Rule, federal jurisdiction over tributaries, lakes, and adjacent wetlands and the proposed definitions of perennial/intermittent streams would be determined based on the conditions during a “typical year.” “Typical year” is defined as the “normal range of precipitation over a rolling 30-year period for a particular geographic area.”

- New definitions for “waste treatment systems” and “prior converted cropland”—The Proposed Rule includes a new definition of “waste treatment systems” that would exclude from federal jurisdiction all components of such lawfully constructed systems designed to actively or passively treat wastewater. The Proposed Rule also clarifies when “prior converted cropland” would be abandoned and, therefore, no longer subject to the existing CWA exclusion.

Opportunities for Comment

If adopted as proposed, the proposed definition of WOTUS would fundamentally alter, and substantially narrow, the scope of the federal government’s authority under the CWA. Interested parties are encouraged to provide comments to the Agencies during the upcoming 60-day comment period. In addition, the agencies have scheduled a public webcast on Jan. 10, and a public listening session in Kansas City, Kansas on Jan. 23.

The agencies are specifically soliciting comments on several key aspects of their proposal, including whether:

- The significant nexus test must be a component of the proposed new definition of WOTUS.

- The definition of “tributary” should be limited to perennial waters and not those with intermittent flows.

- “Effluent-dependent streams” should be included in the definition of tributary.

- The jurisdictional cut-off for “adjacent wetlands” should be within the wetland or at the wetland’s outer limits.

- A ditch can be both a “point source” and a WOTUS.

- The agencies should work with states to develop, and make publicly available, state-of-the-art geospatial data tools to identify the locations of WOTUS.

Continuing Uncertainty

It is important to highlight that the proposed rule, while significant, is far from a final step in what undoubtedly will be a lengthy process to redefine WOTUS. As with the CWR, litigation challenging any final rule adopting all or part of the proposal is certain. For example, litigation regarding the CWR began almost immediately upon finalization of the CWR in 2015 and continues today. Until this proposal works its way through the rulemaking process and the CWR challenges work their way through the courts, regulated parties must contend with state-dependent differences in the scope of federal authority under the CWA. These nuances can have significant permitting, compliance, and enforcement implications.

Babst Calland is actively monitoring this rulemaking and is analyzing how it could affect industrial, commercial and municipal clients across the country.

For the full article, click here.

Institute for Energy Law Oil & Gas E-Report

(by Joshua F. Hall, Nikolas Tysiak and Jason Zoeller)

West Virginia law presents unique challenges regarding jointly owned property in situations where a minority owner cannot be identified, is not available or refuses to join in the leasing of oil and gas. It is not uncommon for oil and gas rights in West Virginia to be owned by members of the same family for several generations, and the result is that an operator may need to approach multiple parties to lease a single parcel. Historically, West Virginia law has placed strict requirements on a lessee in leasing cotenants and required the consent of all parties before oil and gas operations could commence. However, when leasing all cotenants in an oil and gas property is not feasible, there are several statutory options available in West Virginia that may provide relief to an operator, including a new Cotenancy Modernization and Majority Protection Act that was passed this year.

For the full article, click here.

For the full report, click here.

On Friday, November 9, 2018, Babst Calland participated in the Deployment Partner Consortium Symposium at Carnegie Mellon University organized and hosted by Traffic21 Institute and Mobility21 Transportation Center. The Symposium brought together thought leaders in the mobility and transportation space to identify real-world transportation needs, as well as the policy and research challenges that come with advancing technology.

Johanna Jochum, attorney in Babst Calland’s Mobility, Transport and Safety and Emerging Technologies practice groups, spoke on the government panel regarding regulatory challenges at the federal level for autonomous vehicle technology. Ms. Jochum is based in Babst Calland’s Washington, D.C. office, which has direct ties to the federal regulators in transportation.

Babst Calland is a new member of Mobility21’s Deployment Partner Consortium, along with other industry and public partners. Mobility21, the National University Transportation Center for Improving Mobility, aims to research, develop and deploy cutting edge technologies and policies, and develop educational programs to lay the groundwork for next-generation vehicles and mobility services. Read more about Mobility21 and the Symposium at Mobility21 News.

Carnegie Mellon University’s Traffic21 Institute, which is housed in the Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy, was founded on the motto of Research, Development and Deployment encouraging researchers to address real-world transportation needs through partnerships. Since 2012, Carnegie Mellon University has maintained the Deployment Partner Consortium, and it continues that tradition with its US DOT funded National University Transportation Center, Mobility21, with the goal of improving the mobility of people and goods.

“Carnegie Mellon University has been at the forefront of autonomous vehicle technology for many years and continues its thought leadership through Traffic21, Mobility21 and its smart cities institute, Metro21,” said Alana Fortna, Pittsburgh-based litigation attorney and member of Babst Calland’s Emerging Technologies practice group. “Carnegie Mellon University has had such a positive impact on Pittsburgh’s presence in the technology arena, and Babst Calland is proud to partner with the folks who are moving the needle on these issues.”

“There are so many challenges for companies engaging in advancements in autonomous vehicle technology from a federal policy standpoint,” said Ms. Jochum. “We help our clients develop vehicle technology business decisions, given the understandable uncertainties over the current and emerging federal regulatory approach.”

Headquartered in Pittsburgh, Pa., Babst Calland capitalizes on synergies with its Washington, D.C. office in serving the needs of mobility, transport and safety and emerging technologies clients. Babst Calland also has focused law practices in environmental, litigation, construction, corporate and commercial, creditors’ rights and insolvency, employment and labor, energy and natural resources, public sector, and real estate. Babst Calland also has offices in Charleston, W.Va., State College, Pa., Canton, Ohio and Sewell, N.J.

Energy Alert

(by Michael H. Winek, Meredith Odato Graham and Gary E. Steinbauer)

In 2016, U.S. EPA finalized a rule that established first-time federal standards for methane emissions from new, modified and reconstructed sources in the oil and gas industry. The so-called new source performance standards (NSPS) at 40 C.F.R. 60, Subpart OOOOa (Subpart OOOOa) have since become the subject of considerable debate and litigation. Consistent with the Trump administration’s other deregulatory efforts, EPA published a proposal in the Federal Register on October 15, 2018 that aims to reduce the Subpart OOOOa regulatory burden for industry. The agency has already received several comments from concerned citizens who oppose the proposal. EPA will continue to accept stakeholder feedback through mid-December.

Significant Changes to Applicable Requirements

The 52-page rulemaking notice describes several proposed amendments to Subpart OOOOa. EPA is addressing certain issues that were presented to the agency in formal petitions for reconsideration, as well as “other implementation issues and technical corrections” brought to the agency’s attention after Subpart OOOOa was promulgated. For example, it is proposing significant changes to the requirements for fugitive emissions components, including revised leak monitoring frequencies. Whereas the current regulation subjects well sites to semiannual leak monitoring, the revised Subpart OOOOa would require monitoring every other year for low production well sites and annually for all other well sites. The required frequency of compressor station monitoring would be reduced from quarterly to either semiannual or annual. (The proposal includes distinct monitoring requirements for well sites and compressor stations on the Alaska North Slope.) EPA is also proposing to no longer require monitoring surveys at well sites once all major production and processing equipment is removed. These are just a few of the many technical issues for which the agency is seeking public input. Operators should review the rulemaking notice and evaluate how the proposed changes could impact day-to-day operations.

Potentially Overlapping Federal and State Requirements

While EPA may be inclined to relax regulatory obligations at the federal level, states could continue to impose more stringent requirements. For example, Pennsylvania DEP finalized an air permitting package earlier this year that requires quarterly leak detection and repair (LDAR) monitoring for well sites subject to the new general permit known as “GP-5A.” As proposed, the revised Subpart OOOOa would require only annual or in some cases biennial monitoring at well sites. In general, where federal and state standards are in conflict, operators will need to comply with the most stringent requirement that applies. EPA’s rulemaking proposal includes provisions which attempt to address potential overlap in federal and state requirements.

Public Comment Period and Hearing

EPA will accept public comments on the proposed revisions to Subpart OOOOa until December 17, 2018. The rulemaking notice indicates that the agency is seeking comment only on the specific issues identified in the notice. The agency is “not opening for reconsideration any other provisions of the NSPS at this time.” EPA’s related fact sheet indicates that it is still evaluating broad policy issues—such as the regulation of greenhouse gases—associated with Subpart OOOOa. According to the agency, such issues will be addressed separately at a later date.

EPA recently announced that it will also hold a public hearing on November 14, 2018, at its Region 8 office in Denver, Colorado. Interested parties who wish to provide oral testimony at the hearing are encouraged to register in advance by November 6, 2018.

Babst Calland actively monitors federal and state air program developments affecting the oil and gas industry. If you have any questions about the proposed changes to Subpart OOOOa or air quality issues in general, please contact Michael H. Winek at (412) 394-6538 or mwinek@babstcalland.com, Meredith Odato Graham at (412) 773-8712 or mgraham@babstcalland.com, or Gary E. Steinbauer at (412) 394-6590 or gsteinbauer@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

Institute for Energy Law Oil & Gas E-Report

(by Blaine A. Lucas)

Robinson Township Revisited

The parameters of Pennsylvania local government regulation of the oil and gas industry continue to be refined and left uncertain by the ongoing judicial fallout from the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s 2013 decision in Robinson Township v. Commonwealth. In Robinson Township, the Court invalidated two sections of Pennsylvania’s updated Oil and Gas Act (Act 13) limiting the authority of local governments to regulate oil and gas operations. The three-Justice plurality decision was based on a reinvigorated interpretation and application of the Article I, Section 27 the Pennsylvania Constitution, commonly known as the Environmental Rights Amendment (ERA), which states:

The people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment. Pennsylvania’s public natural resources are the common property of all the people, including generations yet to come. As trustee of these resources, the Commonwealth shall conserve and maintain them for the benefit of all the people.

For the full article, click here.

Energy Alert

(by Blaine A. Lucas and Robert Max Junker)

Court Refuses to Adopt a “One Size Fits All” Approach that Would Prohibit Municipalities from Permitting Shale Drilling in Rural Residential and Agricultural Zoning Districts

On October 26, 2018, the Pennsylvania Commonwealth Court published an en banc opinion in Frederick v. Allegheny Township Zoning Hearing Board, et al., No. 2295 C.D. 2015, 2018 WL 5303462 (Pa. Cmwlth. Oct. 26, 2018) rejecting a challenge to the validity of the Allegheny Township, Westmoreland County (Township) zoning ordinance. The Court addressed the contention of oil and gas industry opponents that an unconventional natural gas well pad can only be permitted in an industrial zoning district. After reviewing the detailed record developed in the substantive validity challenge decided by the Township Zoning Hearing Board (Board) and addressing recent Pennsylvania Supreme Court decisions on shale gas drilling, the Court, in a 5-2 decision, rejected this “one size fits all” proposition. It found that state law empowers municipalities to determine where well sites are appropriate and compatible with other land uses within their boundaries.

Background

In 2010, the Township Board of Supervisors enacted a zoning ordinance amendment that allowed oil and gas well operations in all zoning districts as a use permitted “as of right,” provided the applicant satisfied numerous specified standards to protect the public health, safety, and welfare (2010 Ordinance). A use permitted “as of right” requires administrative approval; it does not require public notice or a hearing.

In 2014, CNX Gas Company, LLC (CNX) applied to the Township for a zoning permit to develop an unconventional well pad (Porter Pad) in the R-2 Agricultural / Residential Zoning District and submitted all the information required by the 2010 Ordinance. Once CNX received the zoning permit, three nearby individuals, Dolores Frederick, Patricia Hagaman, and Beverly Taylor (Objectors) appealed to the Board. They challenged the granting of the permit and raised a substantive validity challenge to the 2010 Ordinance. The Objectors claimed that based on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision in Robinson Township v. Commonwealth, 83 A.3d 901 (Pa. 2013) (Robinson Township II), the 2010 Ordinance violated substantive due process and Article 1, Section 27 of the Pennsylvania Constitution, commonly known as the Environmental Rights Amendment (ERA), because it allowed an allegedly industrial use in a residential/agricultural zoning district.

During three nights of hearings before the Board, the Objectors presented Dr. John Stoltz and Steven Victor as expert witnesses. The Board found that neither expert was credible. CNX and land owners presented testimony and called Professor Ross Pifer as an expert on the interplay between the oil and gas industry and agricultural and rural communities in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. The Board found Professor Pifer credible.

The Board’s written decision contained numerous findings of fact related to the qualities and characteristics of the Township, its long history of oil and natural gas development, and the specific operations that would take place as the Porter Pad is developed. The Board rejected the Objectors’ claims that the Porter Pad would have an adverse effect on public health, safety, welfare or the environment. The Board likewise rejected the Objectors’ reading of Robinson Township II, ultimately concluding that the 2010 Ordinance is valid. On appeal to the Westmoreland County Court of Common Pleas, President Judge Richard McCormick affirmed the Board’s decision.

The Commonwealth Court En Banc Opinion

President Judge Mary Hannah Leavitt authored the majority opinion, joined by Judge Renee Cohn Jubelirer, Judge P. Kevin Brobson, Judge Anne E. Covey, and Judge Michael H. Wojcik. Judge Patricia A. McCullough and Judge Ellen Ceisler authored separate dissents.

The Court majority first addressed the Objectors’ substantive due process claim. Judge Leavitt acknowledged that the Objectors did not challenge the Board’s detailed findings of fact as being unsupported by substantial evidence, and that the Board’s credibility determinations were binding on the Court. The Court pointed out that although the Objectors advanced various concerns about natural gas development in their brief, they had not presented credible evidence to substantiate these claims before the Board. Instead, the Objectors merely expressed generalized and speculative concerns about the construction and operation of the Porter Pad. Reviewing its recent decisions in Gorsline v. Board of Supervisors of Fairfield Township, 123 A.3d 1142 (Pa. Cmwlth. 2015), reversed on other grounds, 186 A.3d 375 (Pa. 2018) and EQT Production Company v. Borough of Jefferson Hills, 162 A.3d 554 (Pa. Cmwlth. 2017), petition for allowance of appeal granted in part, 179 A.3d 454 (Pa. 2018), the Court reiterated that objections to construction activities and mere speculation of possible harm are insufficient to sustain an objector’s burden.

In addressing the Objectors’ repeated use of the term “industrial” to describe natural gas wells, the Court observed that the Objectors did not present any evidence to the Board “on what they meant by ‘industrial’ or the significance of that term.” The Court cited to its recent decision in another ordinance validity challenge for the proposition that oil and gas drilling, like farming, is not a heavy industrial use but instead is a use traditionally exercised in agricultural areas, containing temporary components of an industrial use.[1] As a result, the Court agreed with the Board that the 2010 Ordinance does not violate substantive due process.

Next, the Court addressed the Objectors’ contention that the 2010 Ordinance violates the ERA, specifically its first sentence, which states that “[t]he people have a right to clean air, pure water, and to the preservation of the natural, scenic, historic and esthetic values of the environment.” In this regard, the Objectors reiterated the same argument they made under the due process clause – that oil and gas is an incompatible “industrial use” that degrades the local environment. The Objectors also asserted that the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the ERA in Robinson Township II required the Township to engage in an undefined pre-action environmental impact analysis before enacting the 2010 Ordinance.

In analyzing these ERA claims, the Commonwealth Court acknowledged the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s 2017 ruling in Pennsylvania Environmental Defense Foundation v. Commonwealth, 161 A.3d 911 (Pa. 2017) (PEDF). In PEDF, the Supreme Court rejected the three-part test for measuring compliance with the ERA enunciated by the Commonwealth Court in Payne v. Kassab, 312 A.2d 86 (Pa. Cmwlth. 1973)[2] and instead ruled that challenges raised under the ERA should be decided in accordance with its text.[3] Acknowledging that the “precise duties imposed upon local governments by the first sentence of the [ERA] are by no means clear,” the Commonwealth Court ascertained the relevant standard, based on Robinson Township II and PEDF, to be whether the governmental action “unreasonably impairs” the environmental values implicated by the ERA. However, the Commonwealth Court found that Robinson Township II “did not give municipalities the power to act beyond the bounds of their enabling legislation” and that “[m]unicipalities lack the power to replicate the environmental oversight that the General Assembly has conferred upon [the Department of Environmental Protection] and other state agencies.”

The Court also observed that Section 3302 of the Oil and Gas Act preempts municipalities from regulating “how” drilling takes place, and that a municipality may only use its zoning powers to regulate “where” mineral extraction occurs. The Commonwealth Court concluded the Objectors failed to prove that the Township’s legislative decision expressed in the 2010 Ordinance allowing gas wells in all zoning districts “unreasonably impairs” their rights under the ERA, particularly when the record (and the Board’s findings) showed how long gas development has safely coexisted within rural communities, how the land can be returned to its original state once the wells are completed, and how energy extraction can support the agricultural use of land.

The Court next addressed the Objectors’ claim that the 2010 Ordinance violated several provisions of the state’s zoning enabling legislation, i.e. the Pennsylvania Municipalities Planning Code (MPC). Once again, the Court pointed out the conclusory nature of the Objectors’ argument that oil and gas drilling is incompatible with rural uses. The MPC sets forth the detailed public process that a municipality must follow when it amends its zoning ordinance. However, the Objectors claimed that Robinson Township II added a level of analysis requiring the Township to undertake pre-enactment environmental, health, and safety studies in order to satisfy the Township’s obligations under the ERA. The Commonwealth Court rejected this claim and agreed with the Board that such an argument is a novel construction without any foundation under Pennsylvania law.

In its conclusion, the majority opinion recognized that municipalities, if they do elect to utilize their discretion to enact land use regulation in the first place, must balance the interests of landowners in the use and enjoyment of their property with the public health, safety, and welfare. The Objectors’ contention that the 2010 Ordinance will result in oil and gas development anywhere and everywhere in the Township is tempered by the significant setback requirements in Act 13 that remain in effect. In fact, the Board found that these requirements eliminated shale gas development from more than 50 percent of the land in the Township. The Court returned to the “where” versus “how” distinction declared by the Supreme Court and noted that a zoning ordinance expressing legislative decisions regarding where a land use can occur must be affirmed unless clearly arbitrary and unreasonable.

The penultimate paragraph in the majority’s opinion is worth noting here: “Objectors’ objectives in this litigation are confounding. Were they to succeed in invalidating [the 2010 Ordinance], then they release oil and gas operators from the ordinance conditions that relate to noise, lighting, hours, security and dust. Absent [the 2010 Ordinance], CNX’s permit could be invalidated. However, CNX would no longer need a ‘zoning compliance permit’ to operate the Porter Pad.”

Dissenting Opinions

Judge McCullough dissented and would remand the case back to the Board to receive additional evidence as to how the 2010 Ordinance is compatible with the ERA. Reading Robinson Township II in concert with PEDF, Judge McCullough believed that if it was unconstitutional for the General Assembly to permit natural gas development in all zoning districts, so too must it be unconstitutional for the Township to do so through its zoning ordinance. Significantly, she would switch the burden of proof in a substantive validity challenge and require the Township to make an evidentiary showing to prove that the 2010 Ordinance did not violate the ERA. She also opined that the ordinance “should be subjected to strict scrutiny and analysis in the same manner that courts provide to other fundamental rights.”

Judge Ceisler filed a separate dissent noting that although she agreed with much of the majority’s reasoning, she did not agree with the conclusion that the 2010 Ordinance does not violate the ERA. She would find that the 2010 Ordinance facially violates the ERA and does not comport with the Township’s duties as the environmental trustee of all the public natural resources within its domain.

What’s Next?

The Objectors do not have an automatic right to appeal this decision to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. However, within 30 days of the Commonwealth Court decision, they can petition the Supreme Court to consider the case. If the Supreme Court declines to take the case, the Commonwealth Court decision will remain as controlling law. If the Supreme Court accepts the appeal, the parties will brief and argue the case before the Court.

On the same day it heard oral argument in Frederick (November 14, 2016), the same panel of the Commonwealth Court (Judges Leadbetter, McCullough, and Wojcik) heard argument in Delaware Riverkeeper Network v. Middlesex Township Zoning Hearing Board – another substantive validity challenge to a municipality’s decision to allow shale drilling in areas beyond industrial zoning districts. On June 7, 2017, the Commonwealth Court decided Delaware Riverkeeper in an unreported opinion, affirming the validity of the challenged ordinance. Delaware Riverkeeper Network v. Middlesex Twp. Zoning Hearing Bd., No. 1229 C.D. 2015, 2017 WL 2458278 (Pa. Cmwlth. June 7, 2017). As part of its analysis there, the Commonwealth Court applied the three-part Payne v. Kassab test for measuring compliance with the ERA. However, as discussed above, on June 20, 2017 the Supreme Court decided PEDF, which rejected Payne v. Kassab as the applicable test.

In addition, on June 1, 2018, the Supreme Court issued its opinion in Gorsline, referenced above and discussed in greater detail in our Energy & Natural Resources Alert, available here. Although the Supreme Court, in a 4-3 decision, reversed Fairfield Township’s approval of a conditional use for an unconventional gas well pad, it did so on narrow grounds related to the “savings clause” language of the zoning ordinance there, specifically whether the well pad was “similar” to other uses in the applicable zoning district. However, the Gorsline majority concluded with language rejecting the objectors’ contention that oil and gas development was “incompatible” with uses in rural and agricultural districts, thus recognizing that zoning decisions are inherently local matters and local municipalities are empowered to “permit oil and gas development in any or all of its zoning districts.” In addition, the Gorsline majority cautioned that its narrow holding “should not be misconstrued as an indication that oil and gas development is never permitted in residential/agricultural districts, or that it is fundamentally incompatible with residential or agricultural uses.” Gorsline, 186 A.3d at 389.

On August 3, 2018, Supreme Court vacated and remanded Delaware Riverkeeper, directing the Commonwealth Court to reconsider its decision in light of PEDF and the above-quoted language in Gorsline. A decision from the Commonwealth Court is pending.

Babst Calland represented CNX in this matter. For more information regarding issues relating to land use and municipal implications of the Commonwealth Court’s decision, please contact Blaine A. Lucas at 412-394-5657 or blucas@babstcalland.com or Robert Max Junker at 412-773-8722 or rjunker@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

Environmental Alert

(by Lisa M. Bruderly and Gary E. Steinbauer)

In two highly anticipated companion decisions, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ruled that the Clean Water Act (CWA) does not extend liability to pollution that reaches surface waters through groundwater. The Sixth Circuit declined to join the Fourth and Ninth Circuits, which earlier this year held that the CWA regulates discharges of pollutants that reach “navigable waters” after traveling through hydrologically connected groundwater. The conflicting decisions arguably broaden the scope of the CWA’s National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permitting program in the 14 states and 2 territories within the Fourth and Ninth Circuits and narrow the scope of the NPDES program in the four states within the Sixth Circuit. The Circuits’ disagreement on the scope of the CWA makes it even more likely that the Supreme Court will weigh in on this important issue.

Factual and Legal Background

On September 24, 2018, the Sixth Circuit issued a pair of decisions in two cases involving CWA citizen suits brought by environmental groups seeking to hold coal-fired utility companies liable for alleged unauthorized discharges from coal ash ponds or impoundments. Kentucky Waterways Alliance & Sierra Club v. Kentucky Utilities Co., No. 18-5115 (6th Cir. Sept. 24, 2018); Tennessee Clean Water Network v. Tennessee Valley Auth., No. 17-6155 (6th Cir. Sept. 24, 2018). The facts of each case are similar, even though they were appealed to the Sixth Circuit at different procedural stages. Unless specifically referred to in this Alert, we address these decisions collectively.

In Kentucky Waterways Alliance & Sierra Club v. Kentucky Utilities Company (KWA), the plaintiff environmental groups filed a CWA citizen suit against the owner of a coal-fired power plant for alleged violations of the CWA and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA). The plaintiffs’ complaint alleged that two coal ash ponds contaminated groundwater and the contaminated groundwater flowed through karst topography into a nearby surface water. The district court dismissed the plaintiffs’ claims, holding that (1) the CWA did not apply; and (2) the plaintiffs’ lacked standing to bring their RCRA claim. The plaintiffs then appealed the district court’s order dismissing their complaint.

By contrast, the district court in Tennessee Clean Water Network v. Tennessee Valley Authority (TCWN), did not issue its decision until after a bench trial. Like the plaintiffs in KWA, the plaintiffs in TCWN brought a citizen suit against the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) for alleged violations of the CWA and NPDES permit stemming from alleged discharges from a former coal ash pond that was later converted into a dry coal ash landfill and a series of active coal ash ponds. The TCWN plaintiffs asserted that these coal ash disposal units were leaking and contaminated groundwater was traveling through a direct hydrologic connection to a nearby river, in violation of the CWA. Based on the same facts, the district court also found TVA liable for the alleged violations of its NPDES permit. Following the trial, the district court ordered TVA to “fully excavate” approximately 13.8 million cubic yards of coal ash from the units and relocate it to a lined disposal facility. Due to the high costs associated with its remedy, the district court declined to assess a civil penalty against TVA. TVA then appealed the district court’s decision.

The Majority Rejects CWA Liability

While it issued separate decisions in the KWA and TCWN appeals, both the majority and dissenting opinions in the KWA and TCWN appeals (collectively, the Majority and Dissent, respectively) are substantially similar. In both cases, the same two judges (Judges Richard Suhrheinrich and Julia Gibbons) held that the CWA did not cover pollution that reaches surface waters via groundwater. The Majority categorized the plaintiffs’ CWA claims under two separate theories: the “point source” theory and the “hydrological connection” theory.

“Point Source” Theory – Quickly disposing of the “point source” theory, the Majority found that neither the groundwater carrying the alleged pollution nor the karst topography through which it travels are a “point source” under the CWA. A “point source” is defined under the CWA as a “discernible, confined, and discrete conveyance” 33 U.S.C. § 1362(14). The Majority parsed each term within this definition and ultimately held that “groundwater is a ‘diffuse medium’ that seeps in all directions, guided only by the general pull of gravity.” Similarly, even though the karst topography underlying the coal ash ponds may allow the allegedly contaminated groundwater to reach a surface water more quickly, the Majority rejected the plaintiffs’ contention that karst topography itself was a “point source.” In sum, the plaintiffs’ “point source” theory was rejected as inconsistent with the CWA’s text.

“Hydrological Connection” Theory – Calling it the “backbone” of the plaintiffs’ argument, the Majority held that the text of the CWA foreclosed the plaintiffs’ claims under the “hydrological connection” theory. The Majority first focused on the term “effluent limitations,” which are defined by the CWA to include limitations on the amount of pollutants that may be “discharged from point sources into navigable waters.” 33 U.S.C. § 1362(11). Noting that the word “into” connotes directness or a point of entry, the Majority held that “for a point source to discharge into navigable waters, it must dump directly into those navigable waters – the phrase ‘into’ leaves no room for intermediary mediums to carry the pollutants.” Unlike the Fourth and Ninth Circuit decisions earlier this year, the Majority in KWA and TCWN refused to rely on dicta in Justice Scalia’s plurality opinion in Rapanos v. United States, 547 U.S. 715 (2006), finding that Rapanos is not binding in this context and even if it were, Rapanos did not involve the “point-source-to-nonpoint-source” allegations at issue in the Sixth Circuit cases.

The Majority also held that recognizing the “hydrological connection” theory would upend the mutually exclusive regulatory frameworks of the CWA and RCRA. RCRA’s definition of “solid waste” excludes “industrial discharges which are point sources” subject to the CWA’s NPDES permit program. 42 U.S.C. § 6903(27). Consequently, the Majority held that if it were to find the utility companies liable under the CWA, the companies’ coal ash storage and treatment practices would be exempt under RCRA. Moreover, the Majority noted that reading the CWA to cover the migrating groundwater contamination allegedly caused by the coal ash ponds would gut or “leave virtually useless” the EPA’s 2015 regulations governing the disposal of coal combustion residuals (CCR) (e.g., coal ash) in landfills and surface impoundments. See 40 C.F.R. §§ 257.50-257.107.

Although it refused to find the defendants liable under the CWA, in the KWA appeal, the Sixth Circuit ultimately reversed the district court’s dismissal of the plaintiffs’ claim under RCRA.

Companion Dissenting Opinions

In strongly worded dissents, Sixth Circuit Judge Eric Clay disagreed with the Majority’s conclusion that the CWA did not regulate pollution that travels through groundwater before reaching a navigable water and, instead, would allow plaintiffs to file CWA lawsuits under the “hydrological connection” theory. Agreeing with and quoting the recent Fourth and Ninth Circuit decisions, Judge Clay would have ruled that the CWA regulates point source discharges traveling briefly through groundwater before reaching a navigable water. The Majority’s logic, according to the Dissent, would create a “gaping regulatory loophole” by allowing dischargers to add pollutants to navigable waters as long as the pollutants travel through an intermediate medium.

Judge Clay also saw no issues with the CWA regulating the addition of a CCR to a navigable water and RCRA regulating the storage and management of such CCR. Therefore, unlike the Majority, he did not believe regulation under one of these programs precludes regulation under the other. He argued that this interpretation of the two statutes was supported by EPA’s own statements and the Court should defer to EPA’s interpretation.

Clear Circuit Split

The debate over whether groundwater seepage to a water of the United States is regulated under the CWA rages on. The Sixth Circuit, in the KWA and TCWN appeals, declined to join the Fourth and Ninth Circuits in arguably expanding the CWA to cover discharges traveling through groundwater that has a “direct hydrological connection” to a navigable water or “water of the United States.” With a clear split in the Circuits, the odds that the U.S. Supreme Court will decide this issue have certainly increased. In fact, the defendants in the Fourth Circuit’s decision in Upstate Forever v. Kinder Morgan and the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Hawai’i Wildlife Fund v. County of Maui have already filed petitions for certiorari seeking Supreme Court review.

Notwithstanding the differences in opinion among the Fourth, Sixth, and Ninth Circuits, as a result of the KWA and TCWN decisions, regulated parties in CWA lawsuits alleging the “point source” theory and/or the “hydrological connection” theory now have more persuasive precedent as support when facing allegations of an unauthorized discharge under the CWA from inactive treatment ponds, lagoons, landfills, and other similar sources. While the Sixth Circuit in KWA and TCWN did not expressly address whether coal ash ponds were “point sources” under the CWA, it implicitly agreed with the Fourth Circuit’s decision in the Sierra Club v. Virginia Electric Power Company appeal, which Babst Calland addressed in a recent Environmental Alert.

Babst Calland will continue to monitor developments in the citizen suits seeking to expand liability under the CWA and will be watching the Supreme Court closely as it decides whether to weigh in. If you have any questions about the Sixth Circuit’s decisions in KWA and TCWN or how they may impact your operations and compliance obligations, please contact Lisa M. Bruderly at (412) 394-6495 or llbruderly@babstcalland.com, or Gary E. Steinbauer at (412) 394-6590 or gsteinbauer@babstcalland.com.

Click here for PDF.

Environmental Alert

(by Lisa M. Bruderly and Gary E. Steinbauer)

Another three-judge panel of federal appellate judges has ruled on whether a National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit is required for pollutants in groundwater seepage that ultimately reach a water of the United States. Unlike the two other federal appellate court decisions issued earlier this year, this time the federal appellate court held that the Clean Water Act (CWA) did not regulate such discharges, finding that there was no “point source.”